A Loving Definition of Music, part 3

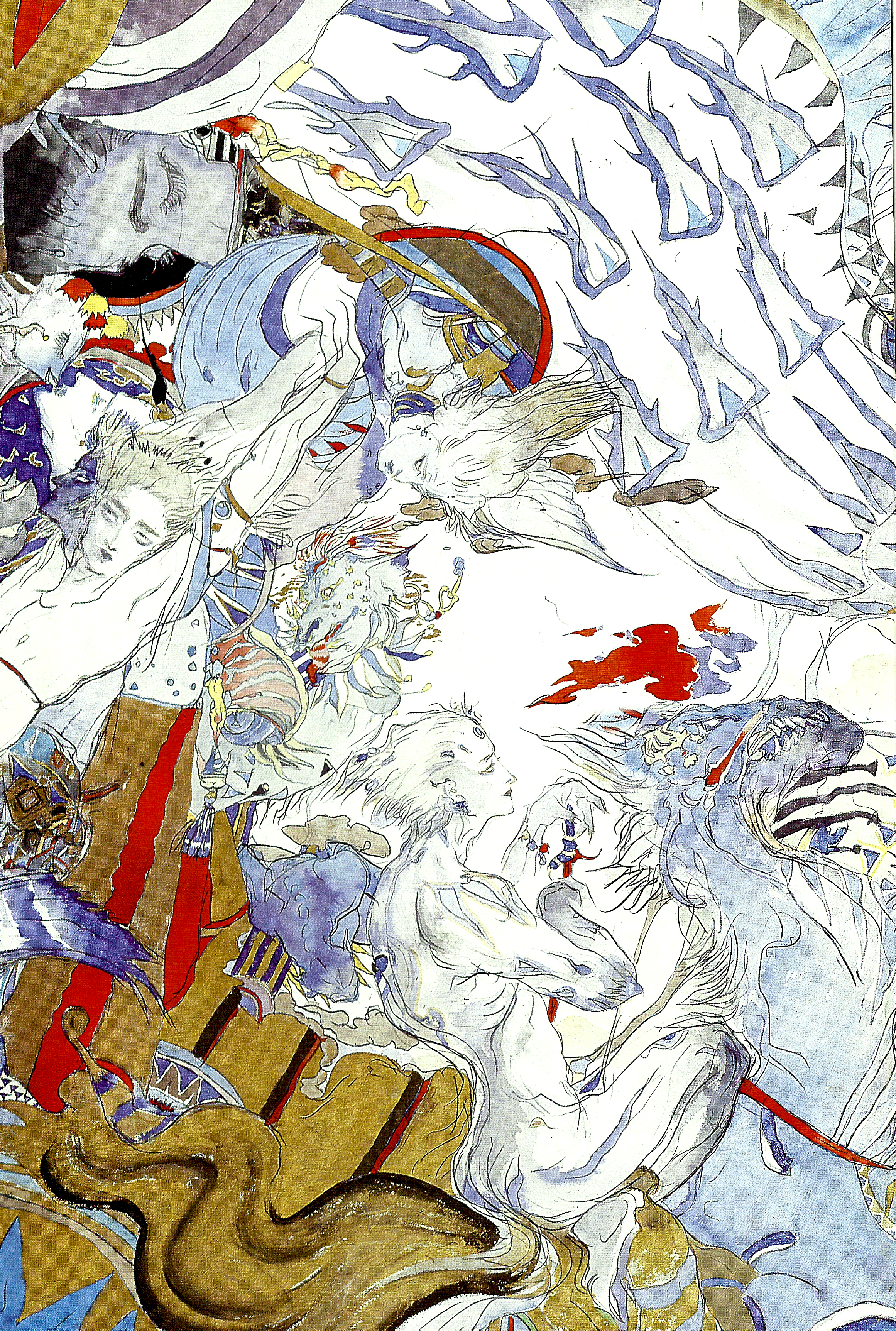

by Yoshitaka Amano

So far we have been rediscovering the old foundation on which a loving definition of music might be built. That foundation is sealed within the infinitely free and ordered life of the Trinity (see part 1) and may only be unsealed to disciples of Jesus by the Spirit (see part 2). It follows that only a disciple of Jesus can build a fully free, fully ordered definition of music with integrity. This is a stark claim to be sure, which fact I will address briefly.

What I am writing hangs on the historicity of Jesus' life, death, bodily resurrection, and ascension as recorded according to eyewitness testimony in the Gospels. A sea of literature has been written on the historical reliability of the gospel accounts which I will not add to here. Rather I would recommend that all readers, skeptical or no, bring their questions to the Gospels themselves, preferably in conversation with an assortment of people. If our prejudices for or against this literature are never challenged, we can hardly trust the reliability of our own conclusions.

As for myself, I find that the more challenging the Gospels become, the more they speak with the ring of truth. They cut like the hardest diamond and so prove their worth. It comes as no surprise to me that a definition of music founded on these documents would cut so deeply. It is the life-saving cut of a surgeon for any who will endure the knife. Without the Spirit of Christ offered in the Gospels, a loving definition of music remains locked in the inaccessible transcendent. Freedom and order may never coincide. Bondage and chaos remain at war in the bedrock of reality.

But in the Spirit we may humbly and prayerfully proceed.

“And chiefly Thou O Spirit, that dost prefer / Before all Temples th’ upright heart and pure, / Instruct me, for Thou know’st; Thou from the first / Wast present, and with mighty wings outspread / Dove-like satst brooding on the vast Abyss / And mad’st it pregnant: What in me is dark / Illumin, what is low raise and support; / That to the highth of this great Argument / I may assert Eternal Providence, /And justifie the wayes of God to men. ”

What is music then? Remember in our previous entry when we considered God as creator and sustainer of the world. Reality is, we concluded, basically an ongoing act of intention on God’s part. This intention applies both globally and particularly, as the impetus of all history and of all phenomena that occur within history. In such a world there can be no such thing as pure noise in the sense of unintended sound. Consider also that God exists at all times in all places. It follows that no sound has ever or will ever go unheard. The riddle of a tree falling in the forest does not apply.

If we put these considerations together, it follows that all sound is made and heard by God with intention. Adding to this that God is Triune, comprised of three Persons, we have the possibility of interpersonal connections and mutual love being facilitated and expressed through the performance and enjoyment of sound. Though not yet a complete definition of music, I submit this as a good description with which to begin, one which applies to all sound everywhere at all times.

Then, are 'music' and 'sound' synonymous? Not quite. Rather they are two different aspects of a single phenomenon. 'Sound' describes waves of motion. 'Music' describes a particular role those waves play in the created order, especially that of forming connections. Sound is what music is made of. Music is what sound is made for.

What does it mean to say that music forms connections? Well think of the musical qualities of language. Think of how music helps us remember the past and imagine the future. Think of how a player becomes one with an instrument or how several players unite to form an ensemble. Think of how a room resonates when music is played in it. Think of the compassion we may feel for centuries-old composers from countries across the world. Think of the litany of corresponding rises and falls that comprise a sine wave. Somewhere in all this is what is meant by connection.

What about music made by humans as opposed to naturally occuring music? Is there any categorical difference between birdsong and flute-playing, between the static of an old vinyl and the fuzzy muffled voice that emerges from it? If music requires intention, and if God's is the only intention to speak of, then all sound basically falls into a single category of divine music-making.

But recall from our previous entry God's radical committment to wills and intentions distinct from His own. This committment is most clearly demonstrated in humanity, especially the humanity of Jesus Christ. (This is not to speak of other living beings such as angels and animals. New categories of music-making might emerge from reflecting on the nature of such creatures.) It is only in Christ, a human will distinct from and perfectly united to God's, that we might speak clearly of human music-making as such.

For Jesus, though fully God, is yet able to express himself fully as a human being. This gives tremendous weight to our activity as humans. We must never confuse human nature with the divine; yet we ought to make much of human capacity to imitate the divine and put it on display in the physical world. In a mysterious way humans make the music of this world more musical by uniting their intentions to the Spirit of Christ.

A disciple of Christ who makes music is woven into the symphony of divine music-making and in fact becomes a kind of "hot spot" in the field of naturally occuring music. The "heat" rises or falls according to our level of investment and love in the act of music-making. Both technique and passion are important, because both invest a person more fully in the music that is being made. No disciple may opt out by saying, "I am not a musician", because even a disciple who listens may reflect God more or less by listening well or poorly.1

If we follow this line of thinking, we may conclude that ensemble music is inherently superior to solo music. After all the more people that are involved, the greater will be the threshold for personal investment and meaning. Again the presence of a Triune God is key to our understanding. The individual who sings out of love with no one but God to listen may do far better than the orchestra that plays for ego and a paycheck. A single heart on fire outshines a thousand hearts of stone.

But the general principle remains that a community holds warmth better than an individual. So we should be encouraged to invite as many people into our music-making as possible, provided that love remains the goal. Remember also that keeping silence is as much a musical choice as making sound. Nothing is wasted when the orchestra stops to let the soloist play a cadenza. The players are fully invested in the silences they produce to make that moment of the concerto possible. The quiet concertgoer and the noisy wedding guest can be just as musically loving given the proper context.2

But if any sound can be crafted into a musical act, why are humans invariably attracted to musical instruments and other methods of "heightened" sound production? Why sing if speaking can be just as loving and just as musical? The answer lies in that word "connection" and in the scriptural concept of Sabbath. We will continue this investigation in the next entry.

1 To be sure a disciple united to Christ cannot reflect God any less than perfectly on the transcendent and spiritual plane. But touching the New Testament category of "the flesh" a disciple may reflect God more or less perfectly in the present world. ↩

2 As a church music leader I am compelled to make this qualification: there is a big difference between keeping silence in order to listen well and keeping silence out of fear of being heard. When Jesus commands God's people to sing and shout, we are beholden to sing and shout the best we can. ↩